My Amoeboid Romance

Hermester Barrington

The next day, I awoke feeling swollen and logy. My forehead was clammy, but the only thermometers I had were in the various terraria and so forth scattered throughout the room, and I was not about to put one of those in my mouth, so I went back to sleep. I awoke again about noon, when the skin on my belly began to itch—pulling up my nightshirt, I saw that the epidermis had a greenish tinge and was cool to the touch. It appeared to undulate, due perhaps to the fact that my body hair had been replaced by some sort of tendril or tentacle which retracted when I stroked it. I lost consciousness then, and came to in the late afternoon with my entire body covered with this new substance.

I arose and looked in the mirror. My irises, previously a shining blue, were now bright red, and the sclera a radiant green, a color I recognized from the local pond in spring. I realized then that last night’s game had become reality, that the organs in my body were being replaced by members of the group known variously as Infusoria, Protozoa, or Protista. The cells of my epidermis, apparently, had become a species of Volvox, a colonial flagellate, and as I watched, the hands with which I stroked my hair—now replaced by Stemonitis, a species of slime mold no longer considered by many to be a species of Protista, but I frequently read outdated guidebooks so perhaps my unconscious mind can be forgiven—stretched their newly-formed pseudopodia outward. They most resembled the magnificent Amoeba proteus, but not having seen specimens this size before, I may have misclassified them.

The transformation proceeded very quickly after that. Sitting at my desk, almost before I could write down the changes, my tongue became Lacrymaria olor, the foraminiferan Discorbis vesicularis replaced my external ears, while a pair of gyrating Urocentrum turbo provided me with a sense of balance—because why not? The cast off tests of Euglypha mucronata formed my choppers, because I’ve always wanted a mouth full of lamprey’s teeth, and this would be the closest I could get. I chose Astrophrys for my eyebrows, because of the name, and for my sperm cells, because of the species’ ruthless determination.

A beautiful blue Stentor coeruleus now serves as my mouth and throat. The colonial vorticellid Carchesium polypinum has colonized its base, serving as my larynx by contracting and expanding in such a manner as to allow me to speak (I don’t understand it, either). From my larynx to my anus, my protozoological demiurge laid nine meters of Ophrydium pipe, except for my stomach, for which Bursaria truncatella was chosen. You may accuse us of lassitude, if you like, but even the protozoan world has its limits.

This intestinal tract is layered with colonial ciliate, I couldn’t say which, providing peristalsis; and my taste buds—their function now performed by a myriad of Klebsiella alligata—have developed a fondness for dirt and dew and creek water, since my internal microbiome has been repopulated by protozoans usually found only in the intestines of the groups Isoptera and Ruminantiamorpha. While I have created many recipes—roof runoff stew, backyard saute, rotting stump roast—I have discovered that my guts and taste buds are happiest when I eat my vegetable matter raw, blended with contributions from the compost heap—rich, dark, damp earth, full of delicious new species for my internal protozoarium! And this methane rich diet makes my nether regions the perfect environment for a hitherto undescribed extremophile amoeboid, Vampyrella flatula—a formal description, co-authored with my wife, Fayaway Maraetoa, is forthcoming in Amateur Protistology CXV:4 (May 2022).

The very rare Teuthophrys trisulca was chosen as a substitute for my pineal gland, while colonies of Noctiluca scintillans have replaced my chakras, though only the one on my forehead is visible to those without the second sight.

There were other changes as well; having recorded them in my journal, I went to bed, for my transformation had exhausted me. Fay came in late that night and, crawling into bed beside me in darkness, snuggled against me; feeling my cool granulated epidermis, she turned on the light and sighed. “I dreamed that this would happen,” she said. “I suppose whatever comes to me when I turn out the light is mine,” she added, and extinguished the lamp, that we might discover the pleasures of prehensile tongue, extensible pseudopodia, and tendrilled flesh together.

Someone at the fateful gathering had said, “I’m sure you will find a use for some species of Vaginicola,” and we laughed. Now a member of that genus serves as my manroot, and, from my own experience, and by Fay’s account, it functions even better than my original equipment, in everything required of it.

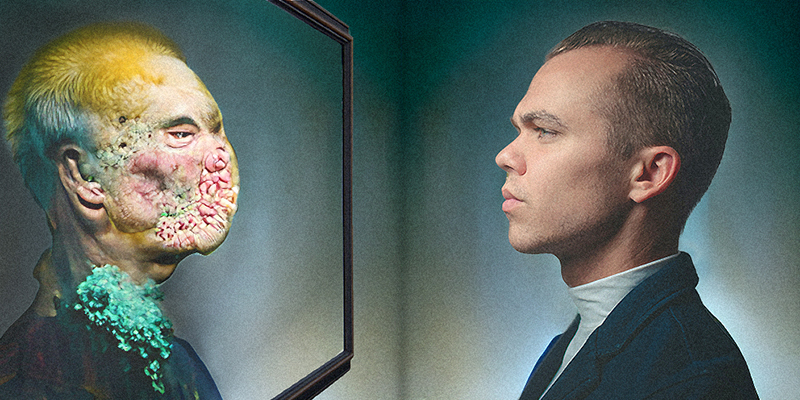

I don’t have lungs as such; my entire body inhales and exhales to irregular rhythms, and the miasma as of a pond slightly stagnant surrounds me, most of the time. Each step sounds as if I were walking through moistened clay, and fragrant puddles mark my passing. I had selected my protozoans for their aesthetics, and each of them, in their own way, is indeed beautiful, but together—Great God!—so monstrous am I become, that only ill fitting clothing allows me to walk the earth unchallenged and uneradicated.

Of my circulatory system I will say little, except to state that members of the amoeboid genus Flabellulidae function as leukocytes—chosen, I suspect, because the species being commensal in oysters, it was unlikely to take over my body as parasitic entamoeboids might—and also, because I like to say the name “Flabellulidae.” Say it three times fast—it might make you laugh. It poses no problem for my fluttering Lacrymaria, but it may for your human organ.

Physarum polycephalum, which has replaced my nervous system, works with the myonemes of a species of Vorticella to coordinate the movements of my new muscles, voluntary and in-. I just discovered that some species of Stylonychia scurry along the Physarum network in some sort of order, but to what end, if any, I cannot say for certain.

I still feel a wide range of emotions from my previous life—I am aroused when Fay asks me rub her shoulders; the works of Remedios Varo give me a frisson of recognition; my body gets up to waltz, unbidden, when I hear the strange time signatures of psychedelic folk—but I am also moved by newer and stranger sympathies.

My longstanding thalassophobia now coexists with joy at the sight of any body of water, causing my own newly formed epidermis to weep slightly. I enjoy basking in the sun in ways that I never had before, thus giving my photosynthetic cells an opportunity to create food. I sometimes awake to find myself laying out on the dew dampened lawn, in the crawlspace under the house, or in the limestone caves in the state park nearby.

It has been some months, I believe, since my transformation was completed, and I seem to have suffered no negative effects. It may be that I am a freak, a nonce symbiosis which will dissolve back into the waters from which I arose after my consciousness fades—or perhaps each of the cells in my new assemblage will retain my consciousness when this concatenation deliquesces. It may be that Fay will bear our hybrid child, or that the same organisms which have occupied my form will colonize others who share my sympathies.

So far none of these things have happened, but I am a sign to those who see only with the naked eye that the kingdom Protista, having been incarnated as human in my body, is prepared to take back the world, after the human species has shambled off into oblivion.

Thanks for reading - but we’d love feedback! Let us know what you think of My Amoeboid Romance on Facebook.

Mythaxis is forever free to read, but if you'd like to support us you can do so here (but only if you really want to!)