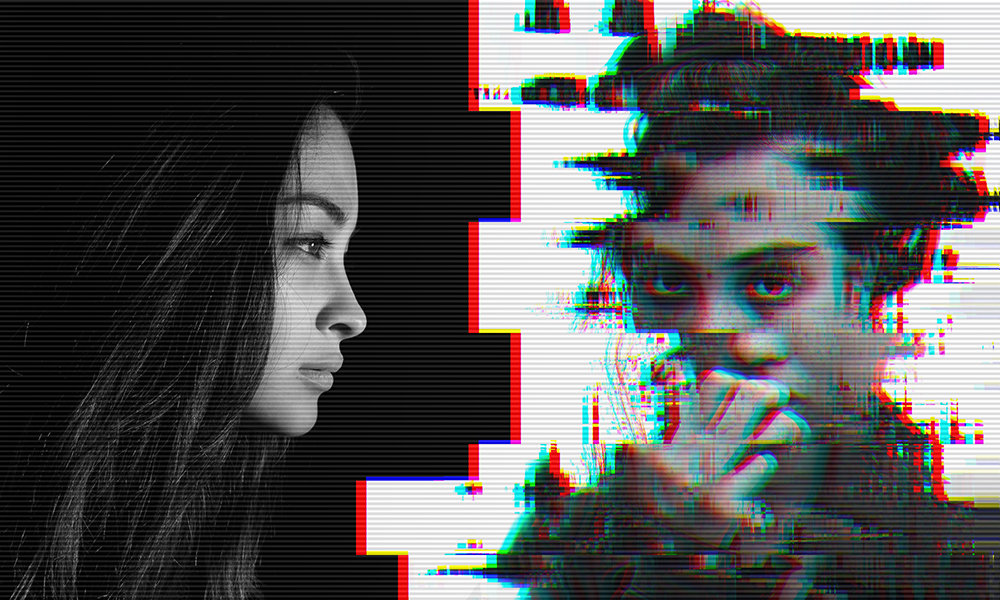

Noise

Owen Leddy

“No, sorry.” Bea was thinking about how cute Lydia’s braids look, about the constellations of freckles that dust Lydia’s cheeks. She catches herself leaning down lower over the back of Lydia’s chair than she really needs to in order to see the data—low enough to smell Lydia’s butterscotch shampoo. She stands straighter.

Stop being a creep, she admonishes herself. Lydia has never shown any signs of being attracted to women—never shown signs of being attracted to anyone, really. I’m probably just making her uncomfortable.

“I didn’t see anything. Can you show me again?”

Lydia sighs. “Oh, come on.” She rewinds the graph showing the signal being received by the radio telescope. “See that spike? Right there?” She pokes the screen again.

Bea resists the impulse to wipe away the fingerprints. “It looks like a random fluctuation to me.” What else can she say?

Bea understands why Lydia is desperate for a breakthrough. Professor Darrow is finally losing patience with her single minded focus on detecting extraterrestrial intelligence, and the comments from her thesis committee are getting increasingly snide. But Bea doesn’t want to lie and lead Lydia down the wrong path, chasing a pattern that doesn’t exist.

“But look, two hours earlier…” Lydia scrolls back: another slight, jagged rise in the radio signal. Bea sighs loudly, and a scowl flickers across Lydia’s face, triggering instant regret. Just having been in the lab a year longer doesn’t give Bea any right to condescend.

“I don’t think—”

“And here! Four hours earlier! And…” She falters. There is clearly no peak at six hours. Malik and Simon, the Darrow lab’s two other graduate students, exchange a look. Malik bends lower over the microcontroller he’s re-wiring.

“Lydia, I think it’s just noise.” Bea means to sound gentle, but it comes out like she’s talking to a fifth grader. “Sorry.” She almost wishes she had lied and said it did look like something worth investigating. Lydia would have wasted a few late evenings, but at least she wouldn’t be mad. “Keep looking, though. I’m sure you’ll find something,” she adds pathetically.

Hours later, just before Bea leaves the lab’s offices for the night, she notices that Lydia has booked a time slot on the radio telescope. Ten p.m. to midnight.

Bea can’t keep the exasperation out of her voice. “Lydia, you’re not seriously going to—”

“It’s way after hours. I can do whatever the hell I want with my free time.”

“Just please get some sleep. I’m worried about you.” Lydia takes care of her needs as grudgingly as an ascetic, choking down undressed salads and occasionally taking a violent little sip from her water bottle like she’s knocking back a particularly burning shot. Lately, Bea has noticed purplish circles under Lydia’s lovely green eyes.

Lydia’s expression softens. She looks up from her computer. “Thanks.” Bea gets lost for a moment in Lydia’s gaze and her twitchy half-smile, then gives an awkward little wave and turns to leave.

How long has this been her nightly routine now? Weeks? Months? Some days she wishes she could just get a decent night of sleep. Occasionally she does. But more often, if she tries, she lies in bed awake for hours, restless and miserable, thinking about what signals might be hitting the radio telescopes at that moment, what new data she could be analyzing instead of lying uselessly in the dark.

She watches the clock on her computer count down the last few minutes until ten o’clock, and then it’s hers: the radio telescope out in Big Pine, California. She types in the coordinates, picturing the forty-meter dish slowly pivoting into place against the moonlit Sierra Nevada, two thousand miles away.

Signal. A wavering line traces its way across her computer screen, plotting the fluctuating intensity of the radio waves hitting the receiver. By the time she’s recorded enough data to start running her analyses, she’s even more convinced there’s something strange about this tiny spot of sky the telescope is pointing at, a flicker of meaning among the static.

She runs her usual suite of statistical tests and finds nothing. The signal is indistinguishable from random white noise. She keeps recording, adjusting the radio telescope tiny fractions of a degree back and forth in case she’s just slightly off, but still nothing emerges except the maddening impression of a pattern she can never quite grasp. Her intuition screams at her that something is there. She spends hours writing code for new analyses, new ways of visualizing the data, typing with jittery fingers after her second cup of coffee. The numbers still offer nothing. But she’s not ready to give up yet.

Under Lydia’s desk, there’s an ancient tube TV that she found among a heap of electronic junk at a yard sale. She bends down and hauls it up onto the desktop, her skinny arms trembling with the effort. She plugs it into the clunky, hand-soldered adapter she built for it, then plugs the adapter into her computer, feeding the signal from the radio telescope into the TV.

She didn’t want to use the tube TV when the other lab members were around—Bea and Malik wouldn’t approve—but it’s a perfect way of looking for repetitions in the raw radio telescope signal without any processing. She knows there are patterns in the data that the lab’s fancy software just won’t show her. As the cathode ray sweeps across the screen hundreds of times a second, any repetitions in the signal will draw an obvious pattern. Lydia feels her heartbeat accelerate in anticipation, imagining the screen filled with beautiful shifting designs, order among the cosmic chaos.

She flips the TV on.

Nothing.

Static.

Random snow.

No, there is something there. There has to be something there. She knows those radio signals are something more than random fluctuations, no matter what Bea says.

She tunes the contrast, brightness, phase… discovers dancing, foaming noise. Finally, her head starts to ache, her eyes water from staring unblinkingly at the screen. She squeezes them shut and grinds at them with the heels of her hands. Iridescent afterimages bloom inside her eyelids—a ring of bright green fading to blue, then red.

Wait… a ring?

If the snow on the screen were truly random noise, the average brightness of a given spot should be uniform all over the screen. The afterimage should be a single rectangle of color, the shape of the whole screen. If it looks like a ring, that means it’s brighter at the edges than the center. The signal isn’t truly random after all.

Lydia drags her heavy eyelids open again. The screen still looks like random snow. At any given moment, there’s no obvious pattern. She stares at it for a while, letting the individual dots bombard her retinas until she can blink and see the glowing afterimage again, cycling from green to blue to red. It’s a different shape now:

N

The letter N? Is that possible? She opens her eyes and blinks again. The afterimage is blurry, the edges not well defined, but it really does look like two bright vertical bars linked by a diagonal slash.

This is crazy. It’s three AM, and I’m becoming delirious. Her hands are shaking. She hasn’t eaten since breakfast, she’s getting lightheaded. But there it is, burning phosphorescent inside her eyelids. Even if it turns out to be an artifact of the cosmic microwave background, she rationalizes, the fact that there is structure to the noise will still be an interesting observation. She fumbles for a notepad to write down what she sees.

ON

After staring at the screen a little longer, different shapes appear in the afterimage, emerging out of the apparent randomness:

ONOT

She turns the brightness on the screen to maximum so that the patterns will burn in faster. She keeps transcribing.

ONOTURN

Words. Actual, recognizable words. Is she picking up a signal from a communications satellite? A plane? Radar monitoring the area says no. There’s nothing all the way out to the exosphere. Besides, why would anyone be transmitting anything so slowly—just one character every few minutes?

ONOTURNAROUN

D follows, it lingers a long time, and when an O and N appear again Lydia is sure that means the D is repeated—once at the end of the message and once at the beginning. The T lingers too, and now her spine is a high-voltage wire as she writes out the full message:

DO NOT TURN AROUND

Lydia sits very still. The lab suddenly seems alive with sound, murmuring and chattering in a thousand tiny voices. Some noises are easily identifiable—the hum of the refrigerator in the break room, the exhaust fan of Simon’s computer, cricket song outside, the intermittent clicking of Malik’s cosmic ray detector—but was that faint rattle always there? Is it just the ventilation? The walls tick and pop, the building breathes, and a low buzz begins that has no source Lydia can think of.

Something in her screams out for her to just turn and look, to confirm that the lab is empty and nobody and nothing is behind her, and it’s only noise.

She can’t.

There’s lightning at the edges of her vision, an eight-piston engine in her chest.

DO NOT TURN AROUND.

Or what?

Lydia tries to stand and can’t feel her legs. She drops, and Bea catches her uncomfortably, squeezing Lydia’s chest so hard she struggles to breathe.

“Bea.” Lydia’s voice is hoarse and groggy. “Something was here.” She struggles upright, leaning on Bea’s shoulders. “Something was there.” Her finger taps frantically on the pad of paper where the coordinates are written.

“What do you mean?”

“Something sent me a message,” Lydia says. “I saw it on the monitor.”

Bea looks at the notepad. DO NOT TURN AROUND.

“It didn’t want me to see… something.”

Bea is so stunned she lets Lydia escape from her grip.

Electric sparks of pain travel up and down Lydia’s legs as her circulation returns. The workbenches are a clutter of microcontrollers, scintillation counters, and spools of solder. The floors are a web of cables and power strips. Recreating a snapshot of what the lab looked like the night before is impossible. Impossible to know whether anything was disturbed, tampered with, displaced. If anything had been there.

“You’re saying someone sent you specifically a message telling you not to turn around, so you wouldn’t see… what? Something here in the lab?” Bea might have felt like laughing if Lydia didn’t look so haggard and shaken. “Lydia, you know that sounds completely absurd.”

“I—” Her indignant glare almost immediately softens to pained confusion. “I don’t know. I don’t know what it means.”

“Well, did you turn around? Did you see anything?”

“I don’t know. I… I thought maybe… It was dark, and I was scared, so I didn’t really… I didn’t want to…” With daylight streaming in through the windows and Bea casually leaning against the workbenches, she could almost believe that the strange signal glowing inside her eyelids was a dream. Almost.

Bea goes to the computer, logs in, and examines traces of the signal from the radio telescope, starting from the time Lydia logged on. She looks at the Fourier transform of the data, the autocorrelation plot, runs a whole suite of machine learning algorithms designed to pluck signal out of noise with exquisite sensitivity, does everything she’s supposed to—everything Lydia has already tried and knows won’t reveal anything.

And then, just like Lydia knew she would, Bea takes off the headphones, shakes her head, and says, “It’s nothing, Lydia. There’s nothing there.” If you can’t quantify it, Bea likes to say, then it isn’t real.

“There is something there,” Lydia insists, knowing she sounds childish, petulant. “I know what I saw.”

“Lydia, come here.” Bea gently takes her by the arm. “You were just anxious, and your imagination was just… Nobody was threatening you. You haven’t slept, I bet you haven’t eaten in a long time. Let’s get you home.”

Lydia wants to resist, wants to find a way to express to Bea the certainty that is already fading from her own mind. But it’s so hard to find the right words, so much easier to let math and software and common sense win out over the fear that shines through her like the cold light of a distant star. She lets Bea lead her to the door.

On their way out, Malik walks into the lab, and Lydia starts shouting coordinates at him without preamble. “Look there. Please—with the radio ’scope.”

Malik just blinks at her for a moment, taken aback. “Is this for the quasar project?”

“Please don’t worry about it,” Bea says. She grabs Lydia’s arm tighter and tries to pull her along.

“Is she okay?” Malik asks Bea.

“I’m right here,” Lydia snaps. “Don’t talk like I’m not here.”

“Malik, please just don’t worry about it,” Bea insists. Before Malik can say anything else, she hurries Lydia through the door with such surprising force that Lydia lets herself be led silently the rest of the way to Bea’s car.

“Are you… Are you feeling alright?”

“I don’t know.” Lydia sits hunched with her chin in her hands. The manic energy that must have fueled her all night has drained away, leaving her looking tired and hollow. She only hesitates for a moment before she lets herself slump back against Bea’s pillows. “I don’t know what happened.”

“You’re going to be fine,” Bea says. “I’m sure it was nothing.”

“I’m not losing my mind.”

“I know.” Bea wonders if Lydia believes her. Wonders if Lydia believes herself.

“I’ll go home in a little bit,” Lydia says, but when Bea comes back a few minutes later with tea and an English muffin, Lydia is asleep on top of the covers.

When Lydia wakes up to early-morning sun seventeen hours later, the first words out of her mouth are, “I’m so sorry. I’ll get out of here.”

Bea grabs Lydia’s arm as she hauls herself upright, confused and entangled by the blankets Bea gently pulled over her after she was already snoring. “Please just rest. I’ll get you breakfast.”

“No, I really don’t want to bother you any more.” Lydia pries Bea’s hand off her arm, but then doesn’t let go of it. She sits dazed, still half wrapped up in the sheets, fumbling for her glasses. “I’m so sorry. I’ve already caused you so much—”

“Stop, stop,” Bea says. “I care about you, and I want you to rest and take care of yourself.” She’s overflowing with emotion, seeing Lydia in this broken state. She grasps Lydia’s shoulders, and Lydia suddenly and convulsively clings to her.

“No, I’m okay,” Lydia still protests. “You shouldn’t have to…” Her arms around Bea’s neck contradict her words.

“Listen, I want to take care of you. Please let me.”

“I don’t know what’s wrong with me.”

“Nothing’s wrong with you,” Bea says, pushing down her worries about Lydia’s mental health. Her arms slide down to Lydia’s waist as Lydia leans into her and puts her chin on Bea’s shoulder.

“Something spoke to me.” Lydia’s voice is a horrified whisper. “Something was there with—” Her hands tighten at the back of Bea’s neck.

“Let’s not talk about it right now. Rest. You can stay here as long as you want.”

“Thank you,” Lydia breathes, and then slowly kisses her, just like Bea has daydreamed so many times. Lydia’s warm lips against hers, Lydia’s fingers gently tracing along her neck—she had thought it could never happen. But Lydia seems to have become a believer in the impossible.

“You do believe me?” Lydia says, when she gently pulls away. “Do you believe what I saw is real?”

Bea hopes Lydia can’t feel her tense up. She feels ambushed. She didn’t want this kiss to have conditions, but she knows hesitation is an answer in itself, so before she can overthink it she says, “Yes, of course I believe you.”

Lydia exhales and relaxes against Bea.

“Thank you,” she says. “Thank you.”

Even if she manages to extricate herself gently enough that Bea doesn’t wake up, she’s paralyzed by the possibilities presented by her phone, lying on Bea’s bedside table. She could call The New York Times or Popular Science or Nature and tell her story. Tell them she knows she has a true positive (such a reassuring, triumphant phrase), no matter what Bea says. She could call Professor Darrow and tell him she’s ready to come back to the lab.

She keeps thinking about the radio telescopes, still pointed skyward, still taking in data—the ears of humanity straining to hear the whispers of the universe. What if whatever it was that threatened her—that warned her—is still out there? What if it tries to reach out again, but nobody is listening?

The first time she told Bea she was thinking of going back, that she wanted to look for the source of the signal she saw, Bea fell silent. In that silence, Lydia panicked. Maybe Bea doesn’t really believe her. Maybe Bea doesn’t want her to go back.

The days since Bea had brought Lydia back to her apartment, since that first kiss, have been some of the happiest Lydia can remember, and that’s exactly what scares her. It makes her want to hold her breath so she won’t disturb the delicate perfection of every moment. When Bea stares at her adoringly or laughs at something she says, she finds herself noticing with surprise that she actually likes herself. She’s been able to eat and sleep more, without first demanding one more hour of work from herself, one more plot of her data, one more block of code.

Until now, her body was always an inconvenient appliance she had to waste time maintaining so she could get on with her work. She had stopped believing that someone she wanted could ever want her back, had never imagined someone could make her feel beautiful. Every day, she feels shocked that Bea still wants to kiss her, to hold her. She’s desperate not to ruin it by saying the wrong thing, by asking too much.

Is believing in what she saw too much to ask?

Lydia waits, lying in bed, staring at the phone on the dresser, considering what would happen if she spoke to a newspaper and Bea found out. Would Bea be angry? Would she make Lydia recant the story, say it was a prank? She can predict all the reasonable arguments Bea would deploy to convince her that it was a false positive: that the supposed signal was so faint it had to accumulate in the afterimages on her retinas; that anyone signaling her would have had no way to correctly guess the sweep frequency of her tube TV; that an extraterrestrial intelligence wouldn’t know how to communicate in English.

Lydia knows she would cave in, but she wouldn’t really believe Bea’s argument—not after seeing those blurred impressions of letters (yes, blurry, but so clearly there) one after another.

By the time Lydia imagines all this, Bea stirs, stretches, turns over, and plants her soft lips over Lydia’s. Each time it happens, Lydia is euphoric and crushingly afraid at the same time. She’s gotten both of the things she has wanted desperately for five years, but she knows she’ll have to give up on one.

A break to recuperate turns into three months of medical leave, turns into leaving the astrophysics program, turns into a job in data science at a marketing firm. Lydia’s lease isn’t up, but her apartment sits empty, and her belongings migrate into Bea’s closet one duffel-full at a time. When Bea comes home from the lab, she always finds Lydia wearing headphones, feet tapping to a fast rhythm. She has to touch Lydia on the shoulder to bring her back from the distant place the music takes her.

At night, Lydia wears earplugs and sets her phone to loudly play white noise, but it isn’t enough. After a few weeks, all Lydia has to say is, “I’m sorry,” and Bea knows it means she should get up and check the closets and hallway again and reassure Lydia that there’s nothing there, that there’s nothing watching her. Lydia doesn’t say what’s going through her head when she startles and tenses in the middle of the night. Bea doesn’t say anything when she sees an online forum for amateur SETI enthusiasts open on Lydia’s laptop.

At three a.m., when Lydia buries her face in Bea’s chest and tries to forget the million tiny sounds she can no longer block out (any noise could be a signal or a warning, her brain tells her), Lydia thinks about asking whether Bea really believes her. She takes in a breath to speak, and lets it out again. She doesn’t actually want to know.

“You okay?” Bea asks, jumpy, hyper aware of the fact that this is the first time Lydia has been back on the University of Chicago campus since her breakdown.

“Yeah. Fine.” Lydia puts on a vacant smile and fusses with Bea’s bow tie and pomaded hair. Is that a nervous twitch at the corner of Lydia’s mouth? Is it significant that she pulls Bea’s tie slightly too tight? She’s nervous. She’s terrified. She’s resentful. Envious. Or it’s nothing.

Bea stumbles through her presentation on the atmospheric chemistry of extrasolar planets, distracted by the way Malik and Simon glance at Lydia and then at each other, the way Lydia avoids making eye contact with anyone. The faculty committee doesn’t fail Bea, even though she thinks she would deserve it. Lydia sits rigidly upright and stares straight ahead through the whole defense. She never smiles once, even when Professor Darrow presents Bea with her diploma and addresses her as “Dr. Martinez.”

Afterward, they go out to Bea’s favorite Indian restaurant for dinner—members of the lab, Bea’s sister, a few college friends—and Lydia hardly touches her mattar paneer. Bea tries not to let her frustration show, tries not to show how much it hurts that Lydia can’t at least put aside whatever conflicted feelings she has about the lab long enough to be happy for her. Afterward, Bea persuades everyone to come back to her apartment, toting the cheapest champagne they could find, and an order of samosas to go.

When they are halfway through the box of samosas, Bea is nodding and smiling at a very drunk Simon’s stories about his roommates. Really, though, she’s listening to a conversation on the other side of the room.

“I’m sorry if it’s a touchy subject,” Malik is saying to Lydia. “You don’t have to talk about it if you don’t want to. It’s just, we were all so worried about you, and I just want to make sure, you know, that everything’s…”

“Yeah, yeah,” Lydia says. “Everything’s fine. Really, don’t worry about me.”

Malik presses. “Was it a health thing, or…?”

Lydia hesitates.

Don’t tell him, Bea silently screams at her. Please, for god’s sake, don’t. Lydia doesn’t have the right to make Bea deal with this right now.

“There was this thing that happened to me. I’m still sort of trying to make sense of it.”

Malik puts a hand on Lydia’s shoulder. “If it’s bothering you, you can always talk to me. You know that, right?”

“Yeah. Thanks. I… Well, I haven’t really talked to anyone about this before, but…”

Simon’s voice rises until he’s almost shouting. “Don’t you think that’s unfair? I mean, what would you do in that situation?”

“I… uh…” Bea realizes she hasn’t heard a single word of Simon’s rant for the last three minutes. “Yeah, no, I think you’re right. Sorry, one second.” She stands and rushes toward Lydia—I’m walking too fast, I know I’m walking too fast. She wants to grab Lydia’s words and cram them back into her mouth.

“I don’t know what it was,” Lydia is saying, “but something showed up on the monitor. I know this sounds unbelievable, but I was scanning some coordinates I looked at for the quasar project, and the signal looked like… like letters. Words.”

Bea forces a laugh and puts her arm around Lydia’s shoulder, displacing Malik’s hand. Lydia jumps as if ambushed. “Had a little too much to drink?” Bea says. I’m giving you an out, she mentally pleads with Lydia. Just take it and don’t embarrass yourself. Bea tries to make conspiratorial eye contact with Malik like she’s letting him in on a joke at Lydia’s expense, but he just stares back at her in wide-eyed alarm.

“I’m perfectly sober.” Lydia points to her untouched wine glass, then carefully removes Bea’s arm from her shoulder.

Bea keeps that fake grin smeared across her face, fully aware of how stupid she looks. “You don’t really mean you received a signal from somewhere, do you? I mean, it was late at night, you were tired…”

Lydia looks almost sick with anger. “Malik seemed willing to listen and talk about what happened. Unlike you.” Bea drops the fake grin, steps back as if slapped. She hadn’t known this fury was fermenting inside Lydia during the months of tactful silence.

Bea can feel her face getting hot as stares turn toward them and other conversations around the room become endangered, then extinct. “Can we not fight about this right now? Everyone’s just trying to have a nice time.”

“Please don’t try to act like you’re being the reasonable one here. I was just trying to explain—”

“I actually should probably get going,” Malik breaks in. “I have telescope time booked early tomorrow.” Tomorrow is Saturday, and Malik almost never works on weekends, but Bea doesn’t point that out. She just nods resignedly as the chorus of excuses begins—a dog to walk, an errand to run before the supermarket closes. In minutes, Lydia and Bea are alone with the half-empty wine glasses and the last few samosas getting soggy in the bottom of the greasy box.

“What the hell was that.” Lydia says flatly. It doesn’t even sound like a question.

“I thought Malik was putting you in an awkward situation, and I wanted to help you out.” The half-truth slips out so easily it scares her.

“You don’t want to be the one with the crazy girlfriend who thinks she was contacted by aliens. You think I’m like those people raving about—” tears choke her, she shouts through them “—about chemtrails and probes and Roswell. You think there’s something wrong with me.”

Bea sighs. “No, I don’t, but other people will. I don’t want you to get laughed at or get hurt.”

“Don’t pretend you did that for my sake,” Lydia spits. “You’re afraid I’ll embarrass you. You’re ashamed of me.”

Bea moves to hug her, but Lydia raises her arms as if to defend herself from an attack. Bea enfolds her anyway. “I’m not ashamed of you. I love you, and I’m so happy and proud that I get to be with you.”

Lydia is silent for a moment. Then she nestles her face into Bea’s neck. “I’m sorry,” she whispers. “I don’t know what’s wrong with me.”

Bea lifts Lydia’s chin to kiss her, doesn’t mind Lydia’s runny nose against her cheek.

She wonders if the way Lydia eventually relaxes into her arms indicates forgiveness or resignation, whether the little squeeze she gives Bea’s upper arm as she pulls away is a reassurance or a dismissal.

She tries to decipher Lydia’s expression as she starts collecting the wine glasses. Are we okay? Are we not okay? But she could read anything in it.

“A short,” Bea comments.

Lydia hangs back, making Bea slow down to keep holding the umbrella over her. The screen transfixes her. Shapes in cyan, yellow, and magenta flash into being and disappear in milliseconds. The colors stain Lydia’s face.

Panic wells up in Bea. She knows that in the months since she and Lydia fought in front of all their friends, Lydia hasn’t stopped believing that something strange, paranormal happened to her. Now the tectonic fault between the two realities that they have been carefully skirting around will open up, and they’ll both fall into the chasm.

“Come on, Lydia. Please.”

They don’t speak on the drive home.

That night, Bea finds Lydia standing outside in the rain at four a.m. in her pajamas, recording the storm sounds, playing them back over and over, obsessively listening for patterns. Bea mentions the word “psychiatrist” for the first time in months, and Lydia berates her for hours, until Bea can’t take it and screeches away in the car, which twenty minutes later slides off the wet road, through a fence, and into a neatly mown front yard.

Bea comes home on foot, soaked—unhurt but too shaken to drive back. Lydia has cooled down. “Who’s the crazy one now?” she teases.

In the moment, Bea laughs and phones for a tow truck. She’ll cry by herself later.

In the car, Bea’s knuckles are white on the steering wheel. She’s painfully aware that the anniversary of their relationship is also the anniversary of Lydia’s supposed signal from beyond, and anything they do to commemorate one will inevitably evoke the memory of the other.

Bea is afraid that walking by the observatory will upset Lydia, but she hardly seems to notice the imposing brick building as its columns, arches, and metal-plated domes loom over them. Their conversation is easy and light—music, books, interesting flowers, and funny bugs at the side of the path. Lydia untangles the chatter of birdsong around them, picking out individual calls and whistling them back to the callers.

“I think they’re responding to me,” she says.

Bea strains to listen, but she can hardly even tell which call Lydia is trying to imitate.

They reach a clearing, a grassy slope well away from the nearest road, and unpack their picnic as the sun begins to set and paints their skin gold. Unwrapping the foil from their sandwiches and pouring wine into paper cups, it almost feels to Bea like they’re back in their first year of grad school—two friends escaping the city lights to appreciate the stars, hiding their infatuation with one another.

When they’ve finished the sandwiches and most of the wine, Bea topples Lydia into the grass, and they make out, Bea burrowing into the wonderful summer smell of sunscreen and bug spray and butterscotch shampoo. For a few minutes, it feels like the distance between them has collapsed. Then Bea opens her eyes for a moment and sees that Lydia’s eyes are already open wide, staring past her into the darkening sky. Bea pulls away and rolls onto her back.

Twilight is fading, and the Milky Way looms. Lydia’s eyes dart wildly across the sky, like a REM sleeper with her eyes open, connecting points of light and wisps of clouds into hundreds of nonsense patterns. Bea wishes she could appreciate Lydia’s attentiveness and curiosity without thinking about the WebMD pages on paranoid personality disorder and schizophrenia that she’s carefully expunged from her browser history.

And maybe she still can. Lying in the cool grass with her cheek nestled against Lydia’s soft hair, it’s easy to let her mind wander and imagine possibilities without limit. Was that tiny flicker of light a satellite passing between two clouds? A meteor? A supernova millions of light years away? Something else entirely? There is so much light, so many flickers and pulses of the universe hitting the Earth every second, that even if Bea imagines every telescope pointed at the sky at this moment around the world, every eye turned toward the stars, they can only capture a tiny fraction of it. There is so much that can never be analyzed or understood, so much lost and forgotten in the glowing chaos of the city.

“It’s so strange,” Lydia whispers. “So beautiful and strange.”

Bea wants to ask her a hundred questions. What are you looking for? What do you see? Do you miss the telescopes and the particle counters? Do you miss seeing the universe in a thousand colors eyes can’t perceive? Or did it torture you, all that data, all that noise in which you could see any pattern? But she senses the peace between them is fragile, so she just takes Lydia’s hand and squeezes it. Lydia, entranced, doesn’t squeeze back.

Someone had to be the first, Bea thinks, to look up and see more than a random stream of stars crossing the sky. Someone had to be the first to see patterns and tell fantastical stories about them. Someone had to notice the order in the comings and goings of planets and comets, in the swirls of gas on the surface of Jupiter. Subtler and subtler patterns that had once looked like randomness and chaos.

Maybe Lydia isn’t wrong. Maybe Lydia is first.

Bea shivers a little, goosebumps creeping over her skin even though the evening is warm. The shadows in the grass around them, the spaces between the stars, suddenly the darkness seethes with disturbing possibilities.

No, she can’t start thinking like this too. She can’t let this continue. She sits up, tugs on Lydia’s hand. “Come on. Let’s go home.”

WE ARE

FORTY-SE

QU

INST

Where had Lydia thought she heard or saw these? In the traffic noise outside their apartment? In the static on unused radio frequencies?

STAR L

AR

M

TAU

There are notes as well, describing sounds that have no name and no source, lights in the night, glitches and bugs—things nobody else would have thought twice about or even noticed at all. Flipping through page after page, Bea stands paralyzed, hearing as if for the first time the murmur of the rain on the rooftop, the gentle clatter of a distant train (or is it the washing machine downstairs), the hum of the refrigerator (or is it the telephone pole outside, or something else). The dense murmur of the city seems to mask something watchful and threatening. Something stirring just below the threshold of pattern recognition.

I’m letting myself get sucked into Lydia’s fantasies again, she berates herself. She doesn’t have time for this. She has papers and grants to review, data to plot and analyze.

She stomps to the kitchen, slamming the door of the bedroom behind her, trying to make enough noise to drown out the whispers of nonexistent messages that Lydia insists are real. She steps on the pedal to open the lid of the kitchen trash, holds the notebook over it.

This is for the best, she tells herself. It’s not healthy for Lydia to keep something like this, something that will keep drawing her into the same delusions. Drawing them both in.

When Lydia flings the door open, Bea startles so badly she drops the notebook on the floor. They stare at each other across what feels like an enormous distance, across the invisible boundary between their two realities.

“You were going to throw it away,” Lydia accuses, as Bea bends to pick it up again.

“I didn’t know you were…” Bea feels like she should be the one getting angry. She’s the one who caught Lydia, discovered her secret. But all she has is this flimsy denial. She takes a deep breath, squeezes her eyes closed. Like if she doesn’t look at it, maybe she can pretend she never saw it. “I just want you to be able to move on, Lydia. You can’t keep obsessing over this."

But Lydia won’t make it that easy. “Don’t act like you were doing it for me. You just want to pretend nothing ever happened.”

Lydia meets Bea’s eyes, her gaze steady. There will be no more apologies, no more tears. Bea imagines Lydia must have fixed the same defiant stare on her disapproving thesis committee when she proposed focusing her research on the dead-end of SETI. She can remember when she loved that part of Lydia: the uncompromising insistence that the universe is full of hidden, unknown things.

“Lydia, you have to let this go.”

“And what if I don’t?” She grabs the notebook of spurious signals, trying to pull it from Bea’s hand.

Bea can’t conceal her frustration. Why does she have to manage the consequences of Lydia’s obsession? Why can’t she admit she needs help? “If you can’t let it go, then you’re going to drive us both crazy.”

Lydia opens her mouth but can’t seem to speak. She lets go of the notebook. Her eyes radiate pain and betrayal, and Bea suddenly realizes what she’s said. “I— I didn’t mean—”

But Lydia isn’t listening anymore. “I know you’re right. I know most people couldn’t possibly believe me, would think there’s something wrong with me. That’s why I’ve never tried to tell anyone.” Her focus snaps back to Bea. “But you. You at least could have believed me.”

I do believe you, Bea thinks about saying, but doesn’t. Lydia would know it was a lie. It’s much too late to offer unconditional faith, unquestioning trust. In the silent moment of Bea’s hesitation, Lydia turns and races toward the back door, and Bea knows something has broken that can’t be fixed.

As Lydia throws open the door, the light of a passing car, or maybe someone’s motion-activated floodlight, silhouettes her, so bright it makes Bea squint and shield her face. Lydia slams the door so hard it doesn’t catch, and in the instant before it bounces back open she’s gone.

“Lydia!” Bea rushes out onto the landing of the back stairs. The alley below is empty. Bea clatters down the stairs and runs into the middle of the alley. She walks out to the sidewalk and looks both ways down the street. Nobody. How did Lydia get out of sight so quickly? Even sprinting, she couldn’t have gone very far.

Bea fires off a quick text, asking Lydia to let her know she’s somewhere safe, and another to Malik asking him to look out for Lydia, but she feels inexplicably certain that she won’t hear anything back.

What if Lydia really disappears? Bea wonders if anyone would think anything of it. A woman vanishes from her girlfriend’s life after a fight—hardly surprising. A sudden parting, a loss of contact, a random event that may never be accounted for. A woman vanishes in a flash of light. Car headlights. Floodlights. A street lamp just turning on. A light in the city doesn’t need to be explained.

The rain has stopped, so Bea sits down on the back stairs, looking up at the few stars the city lights don’t drown out, struggling not to cry. A car alarm shrieks. The telephone wires buzz. A gate clangs. The lid of a garbage can thuds. The city murmurs and hums with a thousand voices. Everything is orange in the glare of the street lamps.

For a moment, Bea convinces herself—as Lydia did so many times—that she can hear something listening to her, like the faint feedback from a microphone left on. “If you’re there,” she says to the traffic and the wind, “if you’re real, give me a sign. Please. Anything.”

But all she can hear is noise.

Thanks for reading - but we’d love feedback! Let us know what you think of “Noise” on Facebook.

Mythaxis is forever free to read, but if you'd like to support us you can do so here (but only if you really want to!)