Special DeliveryGil WilliamsonIs handwritten evidence reliable?

May 2373 - Account from Professor Mrs Kerstin Johansson, (semi-retired) of the University of Uppsala In my job, I see a lot of writing, not just on paper, but carved into stone, metal or wood. As an archaeologist at the University of Uppsala, ancient writing is one of the basic data sources for my science. In particular, handwriting is one of my specialities, which, I suppose, is one of the reasons why Olaf Ekman's Book arrived at my workstation, eleven years ago. Writing by hand is a rarity these days. We see any amount of printed paper, and lots of tablet notes in a variety of font styles, but beyond that... what? People sometimes sketch preliminary ideas on paper. Shopping lists, score cards, yellow sticky notes. The majority of paper manufactured today is used in an absorbent form to soak up or wipe up spills or bodily exudations. You can't write on a nose tissue. I've tried. Writing being such a rarity, I was surprised that the book was accompanied in its mailpouch by a handwritten note on a plain sheet of heavy paper, signed by the Dean himself. It said, in essence: 1. Do not disclose anything connected with this book to anyone other than me. Do not file any data connected with this project on any computer database. Use only a secure, non-networked computer for your report. 2. You are required to analyse the attached book for authenticity of origin and language, both in its basic form and, as far as possible, with reference to the handwritten additions. Pay particular attention to dates. 3. Transcribe into English the handwritten additions to the text. 4. Submit a single printed report of your conclusions to me in person. I was not permitted to retain a copy of the report I submitted, but the task was so unusual that I still clearly remember almost everything about it. Ekman's 'Book' was actually an old bible. We see a lot of bibles, q'rans, little red books and other religious and political tracts in the archaeology business. During most of the history of printing, religious books in particular were produced in huge quantity, so it is not surprising. Besides, in historical times, superstition made people reluctant to destroy holy books, which often survived for many years after their original publication. This bible was a dog-eared volume some one hundred and forty millimetres tall, ninety-five millimetres wide and forty millimetres thick, as I remember. It had a soft cover of black imitation leather, torn and scuffed. It was grubby and it smelled strangely musty, as though it had been in close contact with animals. The paper was extremely thin, presumably to make the volume as physically small as possible. Each sheet was only 0.05 millimetres thick, so that 1000 pages (500 sheets) measured only 25 mm. Bibles were traditionally divided into major sections called 'books', subsections called 'chapters', and short passages called 'verses'. The print was small, in two columns per page, with each Book named, and each Chapter and Verse numbered. The publication date of this Holy Bible was 2145, over 200 years old when I first saw it. It was in English, published in London at the Hackney University Press, and must have been one of the last so-called King James versions published, the earliest examples of which date from the 1600s. By 2145, the 17th century language used was unfamiliar to nearly all speakers of English, and the bible in use was commonly rendered in contemporary language, just as on-line versions are today. I sent samples of the cover, paper and ink of the bible for analysis, without revealing their source. The plastic cover and the paper were the right age, the printing ink correct. I was able to borrow another copy of exactly the same edition from Stockholm University library, and it was identical, other than wear and tear; the physical appearance, the pagination, font, printer's marks, even the few accidental flecks that always used to appear on a printing plate. On balance, forgery of the book itself was very unlikely. However, what made this bible interesting was that almost every blank space - end-papers, margins and chapter breaks - was filled with handwriting in ballpoint pen, whose ink was initially consistent with the age of the entries. Later entries were in a more primitive ink which later turned out to be coffee. The book, or diary, was, in fact, a palimpsest. The original meaning of the bible text apparently meant nothing to the writer. I remember that, at first, I didn't even realise that the handwriting was in Swedish. Swedish is theoretically my native language, but here in the twenty-fourth century, there are few daily speakers of the language. It was hard to recognise, because the handwriting was atrocious. Even after a lifetime of deciphering ancient documents, I found it extremely difficult to read, and the writer, in search of writing space, had filled all the big areas before resorting to margins and column gutters, and the whole narrative was therefore out of sequence, and the writer clearly lost track of dates very early in his account. In my opinion, the language and handwriting style used were consistent with a Swedish male educated within rural Sweden in the early part of the twenty-second century, about two hundred years ago. For the language, I based my assessment on similar documents of comparable age: the vocabulary (especially the paucity of imported English and other foreign words); punctuation; grammar; and sentence structure used. For the handwriting, my clues were letter shapes and connectors, and, particularly, accents and diacritical marks. As to content, the writer calls himself Olaf Ekman. There was no immediate way to verify this. He was unclear where he was living, lacked company, was unclear about his situation but had adjusted to it. The account was long, repetitive and tedious. It also lacked biographical detail. Using parish and census records, I was able to identify more than two hundred possible Olaf Ekmans living in Sweden at the approximate period, but there was insufficient supporting historical data in his written account for a positive identification. Certainly, several of these Ekmans lacked information on date and place of death, but emigration to other countries typically interrupts the life records of individuals living at that time. In conclusion, while I was unable to comment on any possible delusion on the part of Olaf Ekman, the physical book appeared entirely authentic, and the style of the palimpsest content was entirely consistent with Ekman's assertions as to year of writing. Prof. Kerstin Johansson. May 2373. Appendix Some extracts from Olaf Ekman's writings. As I state in the body of this account, the whole is both boring and baffling. Part of the confusion results from the fact that Ekman does not initially reveal that he is living in a supermarket delivery van. Late in the account, he reveals that the bible, which some other driver had left in the cab, was not the only paper available to him, but that he valued the other paper for lighting fires. He would never burn a bible, apparently. However, the ball-point pen he had in his pocket was the only writing implement available. The pen ran out before the available paper in the bible and the last entries are laboriously scratched with something dipped in a dye made from coffee. The van load, luckily for Ekman, was mostly preserved foodstuffs with a few other everyday items and some women's clothing. 1 June 2151: My name is Olaf Ekman. I have been here for about a month, but I do not remember how I came. The last date I clearly remember is 3 May 2151, so I shall call today 1 June. I have shelter, there is more than enough to eat and drink, but my life is empty. I have not seen another person, bird or animal since I arrived. The van is completely out of fuel and the GPS and radio light up but appear to be broken. The solar panels collect a little energy, but not enough to drive the van any distance. Tomorrow I shall walk to the west (the position of the setting sun) in the hope of encountering a neighbour or a road. 12 June 2151: Ten days and I was lucky to get home. The terrain is flat and almost treeless in all directions from here. After two days pushing through alternate stony desert and ankle-deep, flat-leaved vegetation, I came to a low hill, but the view from the top, in all directions, was exactly the same. I had taken enough food for seven days, turned back after three, and missed the van on the way back. It took three days to find it. Perhaps this is Canada. Are there volcanoes in Canada? 20 June 2151: I managed to cut down one of the tall plants, about ten metres high, with a kitchen knife from the van. The wood is soft like a cactus, and very light. There was a box of balls of string in the delivery. I tied a very bright yellow frock to the top of the pole, and managed to fix it to the van as a flagstaff. I will not miss the van next time I explore. I have decided to climb the volcano. I will see more from there. It appeared to take Ekman several months to achieve this objective. The volcano was so far away that he was forced make huge numbers of part trips to set up supply caches en route because he could not carry enough food and water for the complete journey. In turn, this meant that he needed to signpost the route from cache to cache. 20 October 2151: So, in summary, the trip to the volcano was not a total waste of time. From near the top, it was clear that I am on an island, and it appears uninhabited. Although I never see any aircraft, I am building a sign to attract attention and will keep a fire burning day and night in hope of rescue. 25 October 2151: It rains a lot here, with remarkable thunder and lightning. It is difficult to keep the fire lit. It is good that the load includes a whole case of gas lighters. 6 November 2151: The moon looks smaller from here. Maybe it is the flatness of the land. There follow twenty-two years' worth of increasingly sporadic entries, most may be summarised by 'got up, ate tinned stew, it rained, collected fuel for the fire, went to sleep', a pattern which must be a feature of the life of any castaway. The constant fire was abandoned when it took nearly a day to collect a day's fuel. Every so often, when the solar panels had accumulated a little energy, he moved the van a few hundred yards to another area with more fuel. Eventually, he was only a day's walk from the sea, but his attempts to catch fish were unsuccessful. He never saw another living creature on land or in the sea. Latterly, entries were interspersed by occasional complaints of this type: 12 September 2166: Becoming worried that the tins of food will only last a few more years. I have finally tasted the red bush fruit that look like little jugs that I always thought would be poisonous. I was right. They were almost tasteless, but caused terrible stomach pain. So far, there is nothing at all on this island that I can eat except the tomatoes and grapes that still sprout on my dungheap, and I think I brought these here myself! Happily, the rain water, though it tasted strange at first, has always been OK. It should have been a soul-destroying existence, very much like a life sentence in solitary confinement, yet Ekman appears to have accepted it without either complaint or curiosity. There is no self-pity even in the last entry of all: 1 January 2173: Happy New Year. I opened the last tin today - one I have been keeping for a final treat - peaches. I hate to think how much I owe DK-Mart Supermarkets - a whole delivery! I estimate 20000 kg of tinned and packet food alone, not counting the soft drinks, beer and vodka. And all these ladies' dresses and sandals I used when my overalls and boots wore out! There is no more food, so when I get hungry I will eat as many painkillers as I can and fall asleep. I am sorry, DK-Mart, you will never be paid. Let us say that I have taken my salary in kind. Goodbye. Ekman's death occurred two hundred years ago this year. We still do not know how he came to be marooned. Kerstin showed her unexpected visitor into her kitchen. The man had arrived unannounced, presented his identity badge to her entry scanner, and been admitted without delay and without requiring Professor Kerstin Johansson's permission. This was the sign of a very important person. "Coffee?" she offered. "No, thank you. This is your report, recorded recently, is it, Professor?" Kerstin Johansson regarded the rather pale young man with rising suspicion. He had a friendly face, but that meant little these days. He had unrolled a flekskreen, and passed it across the kitchen table. She recognised the article she had posted on the net the previous day. "Who did you say you were?" She had been so surprised at his arrival that she had not read the admission read-out on her entry screen. "Anders Lidén, UN Truth Commission. Your article, is it?" "Yes, but I fail to see the problem." "You are aware that your work on this project was highly confidential." It was a statement, not a question. She suddenly perceived that Lidén's blue eyes were acutely piercing. Her stomach sank. The UN Truth Commission had a reputation for ruthlessness in the pursuit of academics who crossed the line. "Confidential, yes, but eleven years downstream? And it's a sad story, someone marooned for so long, but it can hardly be important. It happened so long ago - two hundred years this year. That's why I wrote the memoir." "And you were given leave to publish by whom?" "No-one. But this is not my original report, which I agreed to keep confidential, just a memoir." He pursed his lips. "Hmm.. A prevarication. And the quotes from your transcript of Ekman's journal?" "They were not quotes! You will probably see differences from the original transcript... I... er... kept images of a few pages and re-translated them." Lidén rolled up the flekskreen and returned it to his hip bag. "A memoir, you say. Could your memory be faulty, do you think?" He was watching her carefully. "I don't believe so. I was careful not to guess anything that I could not clearly remember." "Such as?" "Lab results. Number of journal entries. I don't know. How long the investigation took." "I see." "Look. If the information is still secret, then I'll withdraw the net release." "Oh, it was withdrawn this morning, and cleared from all public caches. There may be a few copies in private hands, but without the original, they lack substance. We can handle that sort of thing." "So, will I be prosecuted for breach of confidentiality?" "Oh, I hardly think so. A prosecution would be too noticeable. No, we want you to publish, but with certain small changes." Kerstin could feel her hackles rising at the prospect of being forced to publish a lie at the request of the Truth Commission. She knew it happened, but not, surely, to archaeologists. "I don't understand. Was this Ekman important?" "You were never told where the book was found?" It was clearly Lidén's turn to be surprised. He immediately appeared less menacing. "No. I wondered at the time, but I wasn't asked to speculate. It seemed shocking that he was never found, but I suppose there are still remote places like that, even today." Lidén deployed his flekskreen again and opened a form. "As things stand, your report is suppressed. If you endorse this official security form, I will give you some information. The form is specific to this information and does not constrain you in any general fashion. If we later discover that you have revealed that information, you will be sanctioned. On the basis of the information I give you, you may decide to publish your report with changes we suggest. Otherwise, it remains suppressed." "In short, I have nothing to lose, but not a lot to gain, either." "True. But you are now fascinated to discover the secret. That's a gain." "All right. I am fascinated." "OK. Look at the screen until the retinal scan clicks, and then say 'I endorse form number ' and read the number on the screen." The familiar formality complete, Lidén began. "The book and Ekman's remains were found in 2268." "But that was, what, nearly a hundred years before it came to me. Yet I remember a sense of urgency." "That is because, even with the fastest transport available, it took nearly a hundred years to get to you." "I don't understand." "Yes you do." "Of course. A space colony." "Pacifica, formerly called HD69830-4. The starship UNSS Shardik was launched in 2080, when it was feared that our planet might soon become uninhabitable. Like the other starships launched in the late 21st, Shardik carried a population of 50000 crew, a self-sustained town. Travelling at an average of approximately one quarter light speed, Shardik arrived in orbit around Pacifica a hundred and eighty-eight years later. A few of the older travellers could remember their grandfathers telling them about Earth, but none had known any environment but Shardik. Most had been Shardik natives for six or seven generations. As you know, a number of starships have failed as a result of accident, breakdown or civil anarchy, but Shardik was a great success." "Yes. I've read about it." "During computer analysis of the aerial survey on the planet Pacifica, shape anomalies were identified. Most anomalies in the survey turned out, on closer inspection, to be unusually regular natural features. However, telescopic images revealed that one island had on it," he consulted his screen, "a rectangular structure some fifteen metres in length and three in width, and, nearby, some arrays of rocks, hundreds of metres in extent and partially obscured by low vegetation, reading 'SOS', a traditional distress signal. A landing vehicle was immediately deployed to the site, and it was revealed that the rectangular object was an antique road vehicle containing the remains of a human being. The human remains and a few personal effects were returned to UNSS Shardik, where they were subject to analysis in their laboratory." He looked up. Kerstin grimaced. "They couldn't read Ekman's journal." "They could read the dates, though. The publication date of the bible. And the expiry dates on Ekman's cans and bottles. And they were not pleased." "I'm beginning to see why." "You and your family for several generations travel for a hundred and eighty-eight years, only to discover that a supermarket delivery vehicle has beaten you to your destination by one hundred and seventeen years." "I see. So Shardik's crew theorised that we, on Earth, had developed a much faster transport system, making their marathon journey and lost generations a bit meaningless." "Exactly. Radio messages to and from Pacifica take forty-six and a bit years each way, so a lively exchange of views is impossible. But we received images of the bible about sixty years ago. Travelling by very fast unmanned capsule, the bible itself arrived together with soil samples and other physical artifacts from Pacifica just eleven years ago, when you saw it." "Presumably, then, UNSA have, indeed, developed a much faster space drive, but do not want to talk about it." "In point of fact, no. UNSA has achieved marginal improvements in ram ion drives, but nothing that would transport Ekman and his truck almost instantaneously. It was concluded at this end that since it was impossible, the crew of Shardik must have contrived an incomprehensible elaborate practical joke, mocking up photographs of the bible, the truck, the food cans." "And then I certified Ekman's book as real." "Exactly." "So how did Ekman get to Pacifica?" "That's just it. It can't possibly have happened. Therefore, it did not happen. Therefore, the whole tale must be a clever fake, and your report must make that clear." Kerstin stared at, or, rather, through Lidén for a few seconds. "No. I don't believe it. Disregarding the fact that a joke like that is highly unlikely, the bible is genuine. I'm sure of it." "Yes, I'm sure it is." said Lidén, "But if the real truth got out, it would have the most depressing effect on morale. Asking you to put a little doubt into the situation is much preferred." "The real truth? All I can imagine is that it was all faked at this end and Shardik's crew made no such discovery." "Not at all. As far as the inhabitants of Pacifica are concerned, it's a historical fact, and the truck is on view there for anyone to see, as you can confirm with your own eyes if you have a couple of centuries to spare." "Are you saying you know how it happened?" "Not in detail, but it is simply another confirmation of a phenomenon that has been happening since the mid twentieth century. The vast majority of these incidents are virtually dismissed. Anyone pursuing them is regarded as a crank, Ekman's case is embarrassing because he turned up a long way from home with supporting physical evidence." Lidén displayed an image of a piece of yellowed paper, printed in Swedish. "What's this?" asked Kerstin, but went on translating aloud, " 'Bureå Weekly News 5 May 2151'. It's one of those local newspapers from country backwaters that survived net news because local events were never reported on the net. The date. It's something to do with Ekman, isn't it?" "This may explain why we have no wish to provide confirmation of the likely explanation." Lidén enlarged a small paragraph at the foot of the page. Kerstin read the brief article quickly. "Ah, small and green, are they?" "Allegedly. We've never caught them in the act." "I can see why me making a mistake is preferable to this." "We hoped you'd see it that way."

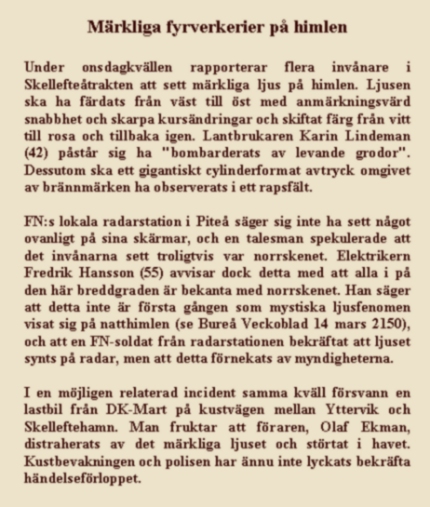

Googlefish translation follows: CELESTIAL FIREWORKS DISPLAY On Wednesday night several inhabitants of Skellefteå reported seeing strange lights travelling across the sky from west to east at remarkable speed, making sharp changes of direction and changing colour from white to pink and back again. Some witnesses reported strange noises. A farmworker, Karin Lindemann (42), alleged that she was 'bombarded with live frogs'. A huge cylindrical depression was found in an oilseed rape field, surrounded by burn marks.  The local UN radar base at Pitea

reported that nothing was seen on their screens, and a spokesman

confided that the villagers had most probably observed the aurora

borealis. Electricity worker Frederik Hansen (55) dismissed this

suggestion, as all local people at this latitude are familiar with the

northern lights. He said this was not the first time that unusual lights

had appeared in the night sky (see Bureå Weekly News 14 Mar 2150),

and that a UN soldier from the radar installation had revealed that the

lights did in fact appear on radar, but were denied by the

authorities. The local UN radar base at Pitea

reported that nothing was seen on their screens, and a spokesman

confided that the villagers had most probably observed the aurora

borealis. Electricity worker Frederik Hansen (55) dismissed this

suggestion, as all local people at this latitude are familiar with the

northern lights. He said this was not the first time that unusual lights

had appeared in the night sky (see Bureå Weekly News 14 Mar 2150),

and that a UN soldier from the radar installation had revealed that the

lights did in fact appear on radar, but were denied by the

authorities.In a possibly connected incident on the same evening, a DK-Mart delivery truck disappeared on the coast road between Yttervik and Skelleftehamn It is feared that the driver, Olaf Ekman, may have been distracted by the strange lights and plunged into the sea. Coastguards and police have so far failed to establish the truth of this theory. © Gil Williamson 2011 All Rights Reserved |

||

Date and time of last update 15:25 Wed 06 Jul 2011 Portions of this site are copyrighted to third parties |

||